As a young photographer in the early eighties, DiRado established an approach that he would return to again and again. For months, or years, he’d immerse himself in a place that drew regulars into loose circles of camaraderie. His first major project documented the summer of 1983 at Bell Pond in Worcester, Massachusetts, an abandoned quarry with a small swimming beach that attracted working-class families and gangs of teen-agers. He’d hang around, get to know people, and sometimes offer to cook them dinner or walk their dogs. Then, at some point, he’d venture that he’d like to take their picture.

When DiRado starts shooting a project, he employs a bulky nineteen-fifties four-by-five view camera, duct-taped in places, and a tomahawk-style flash to light his subjects. Then he captures the moments he wants with a kind of magician’s misdirection. Disarmingly bubbly—with a Boston accent that renders his wife Donna’s name as “Dawner”—he chats away and maintains eye contact throughout the sessions, barely looking down to focus the camera. Despite, or somehow because of, his effusiveness, he often catches his subjects off guard, producing dramatically lit black-and-white images in which people look introspective or melancholy or emotionally undefended. DiRado is frank about the fact that many of his images are projections of his own anxieties. He always gives his portrait subjects prints of the photos but tells them, “Don’t be alarmed by what you see,” because they are as much about him as they are about them.

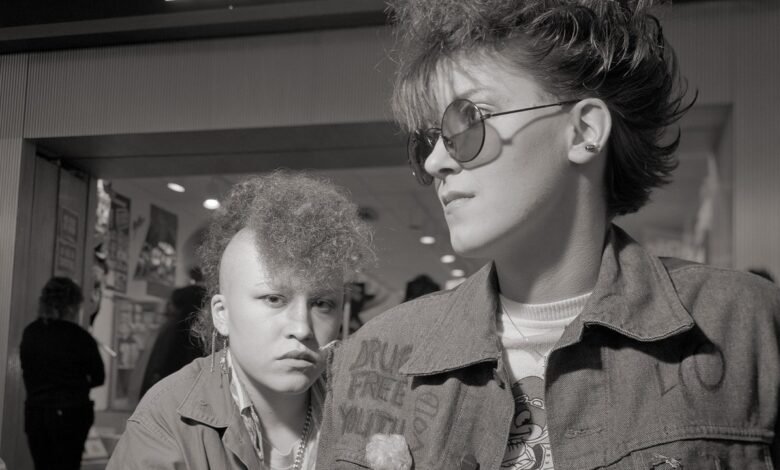

In 1984, DiRado decided that he wanted to chronicle mall life in America, confronting his old fears. “Overstimulation, loss of control—we’re all being manipulated in the mall,” he told me. “We know all that, of course, just like in casinos. Those colors on that sign—somebody thought about that to get you hungry or to buy stuff.” He picked the Worcester Center Galleria as his crucible, a one-million-square-foot mall built as part of an urban-renewal effort in 1971—which meant that, as a local journalist, Brian Goslow, has noted, it “wiped out and replaced nearly the entire downtown core.” By the early eighties, it was otherwise a classic American mall of its time: cavernous, multilevelled, with see-and-be-seen escalators; a fountain that smelled of chlorine and seemed vaguely amniotic (into which pranksters would periodically empty laundry detergent so that it overflowed with suds); wraparound railings that echoed satisfyingly if you banged on them; and all the usual kinds of retail, including a Filene’s, a Jordan Marsh, a record store, a Waldenbooks, and a place where you could get press-on logos for T-shirts that said things like “Disco Sucks” or “I’m with Stupid.” There was a dark, alluring pinball arcade; a giant, slightly scary parking garage; a movie theatre; a food court anchored by an Orange Julius. For two years, from late spring of 1984 to late summer of 1986, DiRado hauled his old camera and his spindly tripod to the Galleria, spending eighteen hours a week inside its self-enclosed, climate-controlled world. He recalls getting to the point where he could touch the front door and feel where the energy would be that day, and where to go first to set up his camera.