Back from the dead, a black hole is erupting after a 100-million-year hiatus

Radio images captured this “cosmic volcano” being reborn at the heart of the galaxy J1007+3540

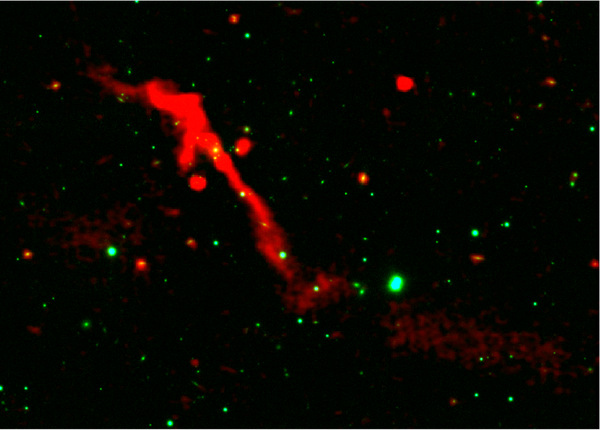

After 100 million years of dormancy, the supermassive black hole at the center of galaxy J1007+3540 is glowing bright.

LOFAR/Pan-STARRS/S. Kumari et al.

Inside an incredibly bright cluster of galaxies, a long-dormant supermassive black hole has come back to life. Radio images captured a one-million-light-year-long stream of star-forming particles and gas emanating from the black hole at the center of the galaxy J1007+3540—which apparently is erupting for the first time in about 100 million years.

“Although some ‘restarted’ radio galaxies are known in the literature, J1007+3540 stands out,” says lead study author Shobha Kumari of Midnapore City College in India. The result recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

J1007+3540 is an uncommonly large example of an episodic galaxy, wherein a central supermassive black hole only intermittently emits prominent jets of particles and gas, almost as if an astrophysical on-off switch was flipped. Researchers say the information they gain from the eruption of this “cosmic volcano” could help them better understand episodic galaxies’ structures, evolution and influence on their surroundings.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ejected jets are a consistent but not ubiquitous feature of the supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies, which, when erupting, are also called active galactic nuclei (AGNs). Many AGNs are thought to be episodic, ebbing as they exhaust surrounding reservoirs of gas, only to surge again when more material drifts within reach. This cycle elapses across thousands of years—glacially slow to us but almost instantaneous on cosmic scales.

That makes episodic activity and the on-off transition difficult to catch as it occurs. Rather than attempting to observe the changes themselves, scientists often analyze the structures within galaxies they think arise from a central black hole’s episodic outbursts. If the black hole is dormant, they look for echoes of its past active phase, such as high-energy light or ionized gas that has traveled farther out from the galaxy’s center. And, of course, if a galaxy’s central black hole is in its AGN phase, like J1007+3540’s, the evidence is obvious.

The radio images of J1007+3540—taken using interferometers at the Low Frequency Array in the Netherlands and the upgraded Giant Meterwave Radio Telescope in India—capture both phases in a single target. The galaxy sports not only a bright newborn jet but also a surrounding surfeit of older material blasted out by past AGN episodes. While other episodic galaxies are expected to have similar structures, J1007+3540’s are especially clear.

“This system is just physically very large, and that makes it more amenable to study in many ways,” explains Niel Brandt, an astrophysicist at Pennsylvania State University. “You can go in and study it in considerable detail.”

One of these details, a faint, fragmented tail of old material extending out into intergalactic space stirred by subsequent outbursts to shine anew, shows how J1007+3540’s AGN phase can impact its cosmic neighborhood—specifically, the gas pervading the galaxy cluster where J1007+3540 resides, known as the intracluster medium (ICM). The shape and brightness of the rekindled tail trace the complex interactions that occurred between the AGN’s ejected jet and the ICM as the jet propagated outward.

“These observations help us understand that the relationship between a galaxy’s jets and the cluster environment is very dynamic,” says Vivian U, an astronomer at the University of California, Irvine. “The jets don’t just carve a path through empty space—they are constantly shaped and changed by the gas they encounter.”

There is still a lot left to learn about how interactions with the ICM can feedback to change the form and behavior of a galaxy’s jets, all of which can spark (or suppress) the creation of new generations of stars. Somehow the flicker and flutter of AGN at the hearts of galaxies may dictate whether they shine for eons or fade to starless black.

“The oddballs are exciting,” says Phil Hopkins, a theoretical astrophysicist at the California Institute of Technology. Observing unusual cases like J1007+3540 gives researchers the opportunity to test and improve their models of how this majestic process unfolds.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.