Novel payment systems based on blockchain networks promise to redesign financial architecture, but a notable concern about these systems is whether they can be made interoperable. This concern stems from the concept of the “singleness of money”—that payments and exchange are not subject to volatility in the value of the money itself. Volatility and speculation can arise from the payment medium, which may have speculative characteristics, or from frictions that undermine the ability of one or more payments systems to interoperate. In this two-part series, we outline a framework for analyzing payment system interoperability, apply it to traditional and emerging financial architectures, and relate it to the ability of the payment systems to maintain singleness of money.

What Is Payments System Interoperability, and Why Do Central Banks Care?

For purposes of our posts, we define payments system interoperability as the ability for users belonging to one system to exchange information and value with those belonging to another system. The degree of interoperability is affected by the level of friction involved with settling transactions across more than one payment system.

One reason central banks care about interoperability is that it supports the singleness of money. It does so by bolstering economic forces that ensure that representations of identical claims across multiple systems, including commercial bank money, are treated at par.

The Pillars of Interoperability: A Framework

Interoperation between payments systems can be complex, and the degree to which interoperability is achieved varies according to the satisfaction of multiple pillars that we broadly divide into legal, technological, and economic considerations.

- Legal Pillar: Ideally, the rules governing payment systems that seek to interoperate are uniform, so that users can transact across systems with a high degree of certainty and consistency. Statutes and regulations underpinning payments across multiple systems should not conflict in such a way that the rights and obligations of parties vary unexpectedly solely because completing a payment requires more than one system. System rules and other contracts can supplement underlying law and help to navigate differences in underlying statutory or regulatory schemes. In practice, however, the rules of connected systems may be different, and if so, parties need to consider whether differences in applicable statutes, regulations, or terms governing a payment as it moves across payments systems creates uncertainty or inconsistencies that result in material risk.

- Technical Pillar: The technical design of a network and the level at which different systems share a common technical component or set of standards can dictate the level of interoperability a network may achieve. Technical interoperability takes many practical forms, including data standardization, common clearing/settlement protocols, and synchronized communication between systems. Examples of standards that support interoperability include messaging standards, such as ISO 20022, and token issuance standards like ERC 20.

- Economic Pillar: Legal and technological choices imply different costs to users. Economic incentives determine how effectively financial and technological service providers facilitate interoperability given the legal and technological environment. These incentives consequently drive adoption and coordination (for example, in the case of mobile payments). In particular, the nature of frictions, the parties harmed by the lack of interoperability, and the ability to monetize interoperability can affect the likelihood of private solutions emerging to develop and implement interoperability.

Payment System Evolution, and Interoperability in Traditional Payment Systems

The banking system in the United States offers a useful example for outlining considerations for interoperability. Banks can be viewed as private payment providers that maintain balances that can be transferred to effect payments in commercial bank money. Payments between customers of a single bank can be executed and settled internally. However, payments between banks require a third party, such as a payment system, to act as a hub. Payment system operators must effectively manage volatility arising from credit and/or liquidity risk.

The Federal Reserve Banks were created, at least in part, to reduce volatility and inefficiencies in the U.S. payment system by performing clearing and settlement functions. The Reserve Banks’ introduction into the payment system in the early twentieth century was accompanied by a statutory mandate to clear checks handled by Reserve Banks and drawn on depository institutions at par.

This mandate, along with the Reserve Banks’ authority to handle checks drawn on any bank or trust company and settle in central bank money, reduced the need for complex correspondent bank clearing and settlement arrangements that had introduced volatility into the system. Although the Reserve Banks’ intervention in the check collection system is not typically characterized as an effort to interoperate, it was designed to cure many of the same problems—the need to efficiently exchange instruments, to stabilize value, and to connect disparate networks. Importantly, from the standpoint of households and firms, the Federal Reserve solidified the singleness of money issued across all depository institutions.

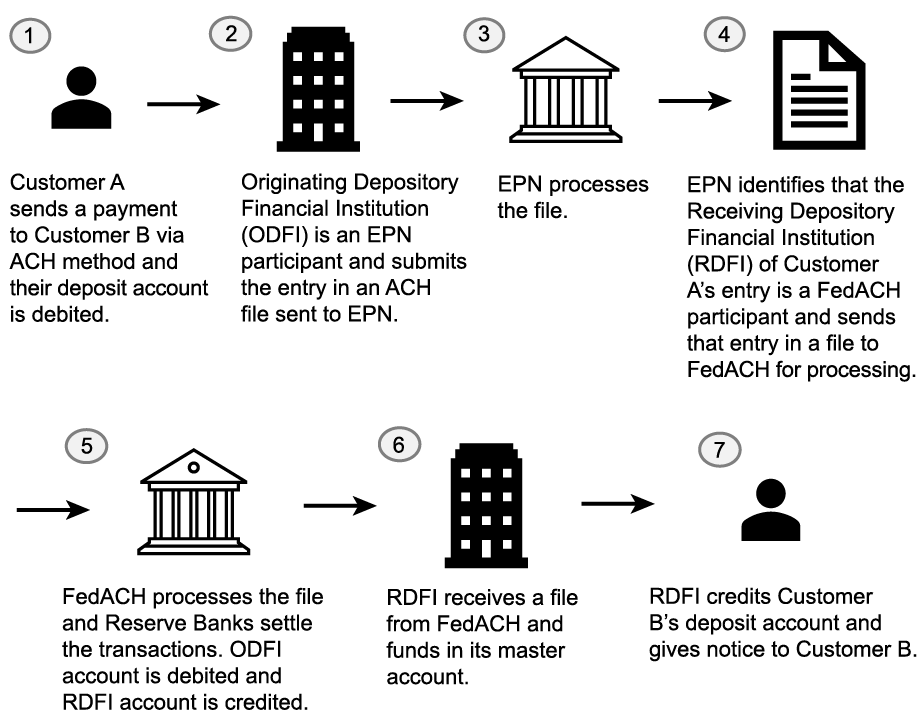

The central role of Reserve Banks in settling and clearing checks evolved with the advent of electronic systems, first through the support of nationwide outgoing government payments via a series of regional automated clearinghouses (ACH) operating sites, and soon after through linkage of Federal Reserve and private-sector clearinghouse sites to establish nationwide reach for commercial payments. These arrangements were the precursor to the Reserve Banks’ current system, the FedACH® Service. The Reserve Banks continue to interoperate in a truer sense than check collection in several respects—namely, because they connect depository institutions that are FedACH participants, they exchange messages and other information with their private-sector counterpart, The Clearing House’s (TCH) Electronic Payment Network (EPN), and they settle for participants in both systems.

Applying the Interoperability Framework to ACH Systems

For the FedACH Service and EPN to interoperate, the two system operators need to manage the operational complexities of the arrangement. Their effort also creates a broad network of users and simplifies the user experience. Payers like employers, through their payroll providers and banks, can reach nearly every person with a U.S. dollar bank account without the need to join multiple networks.

- Legal Pillar: From a legal standpoint, interoperation between the FedACH Service and EPN carries with it a high degree of consistency and certainty. The two services are governed by a common set of core statutory, regulatory, and contractual rules that provide a foundation for interoperation. In particular, transactions through both systems are governed by rules set forth by Nacha (an industry-setting body for ACH payments); commercial credit items handled in both systems are subject to the Uniform Commercial Code’s Article 4A; consumer rights associated with transactions handled by either system will not vary; and the bank participants in both systems are subject to similar chartering, licensing, and regulatory schemes.

- Technical Pillar: The FedACH Service and EPN interoperate on a technical level, enabling banks participating in one network to send payment instructions to banks participating in the other network. We provide an illustrative example of the technical interoperation between the FedACH Service and EPN in the chart below.

A high degree of technical connectivity between these ACH operators is supported by numerous key components, such as operating rules, guidelines, and standard messaging formats for ACH services, which are set by Nacha. These components provide a high level of consistency across ACH operators. They also provide participants with a means to process and settle payments in central bank and commercial bank money, helping to avoid frictions or volatilities that could arise from less efficient networks.

How Do the FedACh Service and EPN Interoperate?

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Economic Pillar: The Federal Reserve spearheaded the initiative to achieve interoperability between Reserve Bank systems and regional ACH associations. The Fed had strong incentives to connect disparate systems with the goal of broadening the reach of the ACH network and enhancing payment functionality of the current FedACH Service. In the current state, EPN maintains a smaller customer base than the FedACH Service but serves some of the largest institutions that represent TCH’s owner base. Interoperability between the two networks creates value for the entire banking system, including for smaller banks that may prefer the Reserve Banks as a service provider over one owned by their larger competitors.

From the end-user perspective, an ACH system that fully connects the banking system helps to preserve the singleness of money in the era of electronic payments. The Federal Reserve helped achieve this by interoperating with its private sector competitors, consistent with the requirements of the Monetary Control Act of 1980, which established cost-recovery expectations for Federal Reserve services, in part to avoid crowding out private-sector innovation. This model, which continues to mold the Fed’s implementation of ACH payments today, helps foster competition and private innovation while reducing payment frictions that might deteriorate the singleness of money.

Summing Up

In the case of commercial bank money, payment system interoperability works in the background so that consumers can make payments without concern for the underlying banking network and arrangements between payment systems. Payers like employers can reach nearly every person without the need to join multiple networks. In this way, interoperability ultimately contributes to supporting the singleness of money. A culmination of legal, technical, and economic factors determines the level of interoperability. We explore interoperability of blockchains and its impact on the singleness of money in our next post.

Jon Durfee is a product manager in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s New York Innovation Center.

Michael Junho Lee is a financial research economist in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joseph Torregrossa is an associate general counsel in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Legal Group.

How to cite this post:

Jon Durfee, Michael Junho Lee, and Joseph Torregrossa, “An Interoperability Framework for Payment Systems,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 27, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/03/an-interoperability-framework-for-payment-systems/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).