Public permissionless blockchains are designed to be censorship resistant, meaning access to the blockchain is unhampered. In practice, different blockchain ecosystem actors (such as users, builders, or proposers) can influence the degree to which a blockchain is resistant to censorship. In a recent Staff Report, we examine how sanctions imposed by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on Tornado Cash, a set of noncustodial cryptocurrency smart contracts on Ethereum, affected Tornado Cash and the broader Ethereum network. In this post, we summarize findings regarding sanction cooperation at the settlement layer by “block proposers”—a set of settlement actors specifically responsible for selecting new blocks to add to the blockchain.

What Is Tornado Cash?

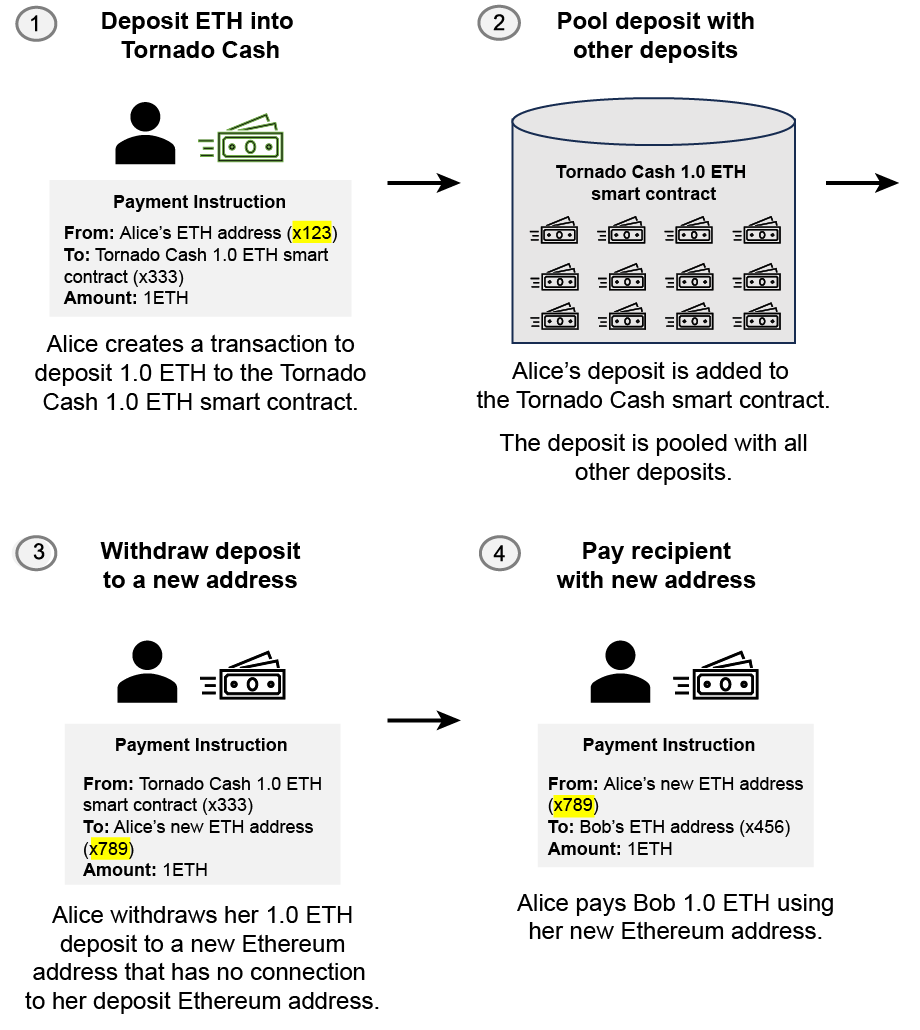

Tornado Cash is a set of smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain, a public permissionless blockchain that allows anyone with internet access to interact with it. Due to Ethereum’s open nature, all transactions are public record. Tornado Cash aims to provide transaction privacy to users by sitting in between payment chains to obfuscate links between payers and payees. Tornado Cash works by creating omnibus accounts, or pools, that specify deposit sizes and tokens and stablecoins (such as 1 ETH, 10 ETH, 100 ETH, 1 USDC, 10 USDC, and so on). To deposit funds into these omnibus accounts, or “pools,” a user transfers a specific deposit of cryptocurrency (1 ETH, for example) to the specific Tornado Cash pool, and attaches a secret key to the transaction that only the user knows. The Tornado Cash smart contract grants anyone who knows the key the rights to withdraw funds from the pool at a later date through any account. The Tornado Cash smart contract does not custody the funds while the funds are maintained in the pools. See the chart below for a stylized depiction and Nadler and Schär (2023) for a more technical overview of Tornado Cash.

A Stylized Example of a Tornado Cash Transaction

Tornado Cash usage continued to rise through 2022 and, notably, it was used by criminals. For example, in early 2022, blockchain project Ronin announced the theft of cryptocurrencies valued at more than $600 million. Lazarus Group, the North Korean hacker group responsible for the hack, funneled stolen tokens to Tornado Cash. On August 8, 2022, OFAC, an agency within the U.S. Department of the Treasury that maintains and enforces sanctions policy for the United States, announced sanctions prohibiting “all transactions by U.S. persons or within the United States” that involve Tornado Cash assets.

Sanctions broadly apply to U.S. persons, entities, and those with forms of affiliations. Hence, not all users and settlement actors are required to comply. Given the pseudonymous nature of Ethereum, we view our analysis as examining cooperation, rather than compliance, with the sanctions. We define cooperation as “behaving in a way that does not facilitate the processing of Tornado Cash transactions.” An important set of settlement actors are proposers, who have the ultimate rights to select the block appended to the blockchain. We analyze the cooperative behavior of the top ten Ethereum proposers, who account for over 50 percent of validated Ethereum blocks, from January 2020 to December 2023. Our analysis is based on on-chain Ethereum transaction data from Dune, a cryptocurrency data platform, and Amazon Web Services’ (AWS) Public Blockchain Data.

Analyzing Cooperation at the Settlement Layer

Ethereum settlement is currently organized in a proposer-builder separation (PBS) structure. Under PBS, transactions submitted by users are bundled into blocks by builders. Builders then offer their blocks to proposers (validators), who have the rights to choose the next block to be appended to the blockchain. In other words, proposers actively choose who to source blocks from (including the possibility of building blocks themselves). Thus, block proposers play an integral part in resisting external censorship as they exercise discretion on which builders to work with, and thus influence the nature of transactions settled on the Ethereum ledger.

In this post, we summarize some key findings pertaining to impact of Tornado Cash sanctions on the behavior of the top 10 proposers, and we investigate whether these proposers actively exclude Tornado Cash transactions.

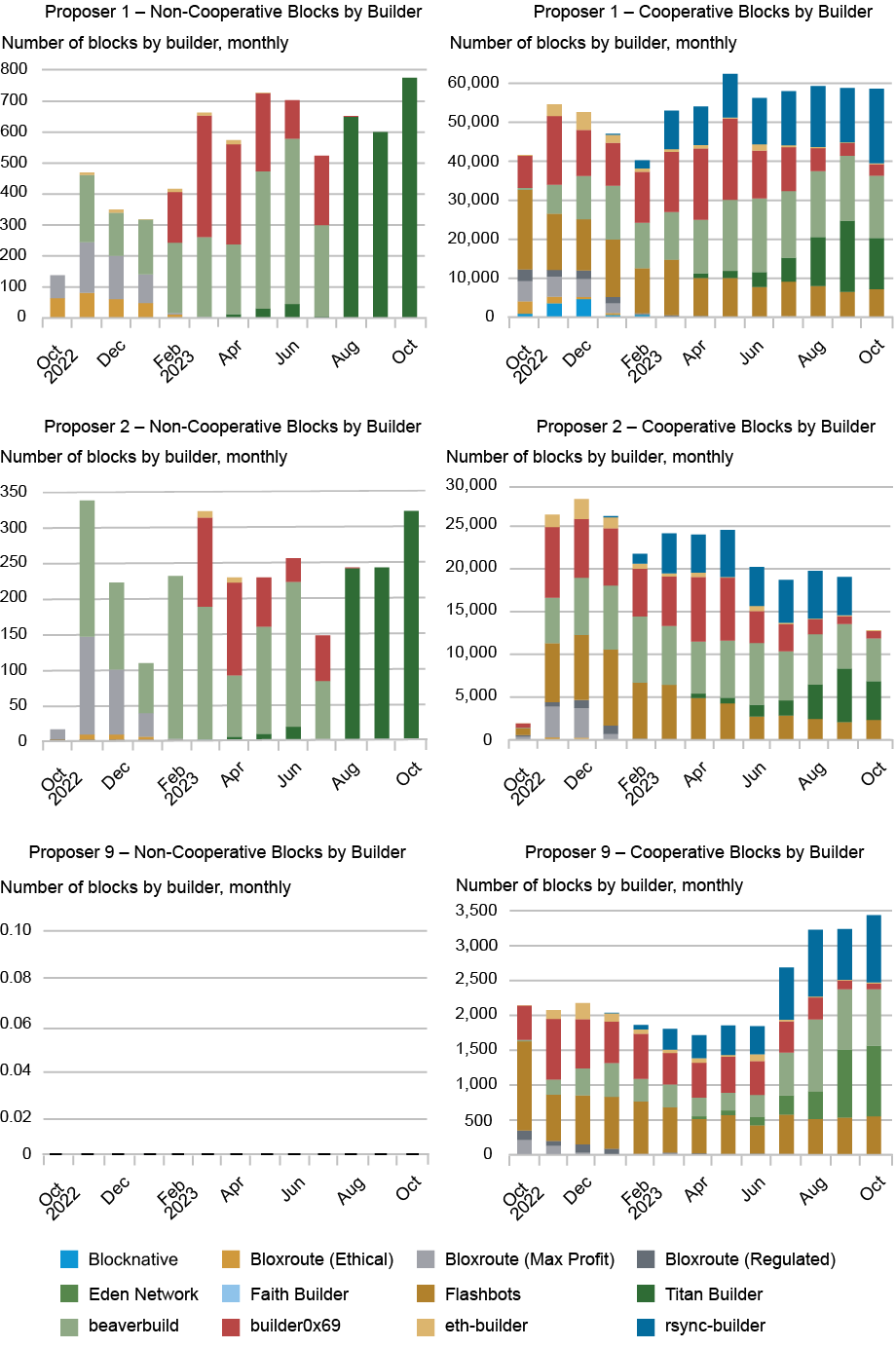

First, we find a wide spectrum of sanctions cooperation among proposers. At the monthly frequency, the number of validated blocks containing Tornado Cash transactions varies significantly across proposers, ranging anywhere from zero to more than 700.

Interestingly, we find that individual proposers maintain remarkably consistent cooperative stances over time (for example, to choose blocks that exclude Tornado Cash transactions), in contrast to builders, whose stances evolve dynamically in response to legal developments. Notably, the top two proposers by block share (Proposers 1 and 2 in the chart below), together accounting for about 40 percent of blocks, validated non-cooperative blocks (in other words, blocks that include Tornado Cash transactions).

Level of Cooperation Differs Across Proposers

What Explains the Non-cooperative Stance of the Largest Proposers on Ethereum?

One possible reason for proposers to continue to validate non-cooperative blocks could be that it is operationally challenging or costly for them to cooperate. In principle, proposers are not able to see the individual transactions included in a block offered by a builder; they select blocks based on the identity of the builder and fees associated with the block. Consequently, a proposer cannot technically verify whether a block is cooperative or not.

In practice, however, this does not appear to be a relevant constraint. First, we observe proposers (for example, see Proposer 9 in the chart below) who consistently process cooperative blocks throughout our sample period. In addition, while it is true that proposers are not able to examine the transactions constituting the block, the identity of the builder is often sufficient in determining cooperation. Starting from August 2023, nearly all non-cooperative blocks validated by Proposers 1 and 2 are provided by a single builder, Titan Builder. More generally, since we find predictability in the cooperative stance of builders—and in some cases, public disclosure on their cooperative stance—the possibility of operational challenges to cooperation by proposers is diminished.

Another argument is that “tokenomics” is in play. In principle, Ethereum is designed to draw diverse participants through monetary incentives. If monetary incentives are the key drivers, we should expect fees associated with non-cooperative blocks to be higher than those for cooperative blocks. We find no evidence that this is the case. In fact, we find the opposite: non-cooperative blocks in our sample consistently offer lower fees, with a discount ranging from 15 to 23 percent, depending on estimates.

Can Public Blockchains Resist Censorship?

Public permissionless blockchains, like Ethereum, are intended to be censorship resistant. However, even blockchains with broad user bases, like Ethereum, are apparently not immune to the potential for certain transactions to be excluded due to external pressure. In our sample, we see a mixed cooperative posture to enforcement at the settlement layer by proposers, and more importantly, we observe no change in postures.

In light of our evidence that cooperation is not difficult, coupled with the fact that the motives for non-cooperation are not financial, our results suggest that the censorship resistance of the system is reinforced by the large players who value censorship resistance as a primitive feature. Further, concrete design features—such as financial incentives, which are intended to permit the expression of views, however controversial—do not appear to be effective in strengthening censorship resistance.

The regulatory and legal framework for decentralized systems is yet to be determined, evidenced by the recent court decision that overturned previous rulings regarding OFAC’s sanctions on Tornado Cash. These developments further showcase that transactions transparency and choice at the nexus of block builders and proposers is a critical research topic for the Ethereum community, which aspires to maintain a censorship-resistant settlement layer. It remains to be seen whether the Ethereum community introduces systematic controls and processes to ensure all transactions at the settlement are settled, irrespective of regulatory regimes.

Jon Durfee is a product manager in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s New York Innovation Center.

Michael Junho Lee is a financial research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jon Durfee and Michael Lee, “How Censorship Resistant Are Decentralized Systems?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 14, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/02/how-censorship-resistant-are-decentralized-systems/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).