Concealing some of the information on job applications led to more women being hired.Credit: Christopher Ames/Getty

In 2017, when Sherri Christian returned to her institution after a year-long sabbatical, she looked around the biochemistry department and realized that she was the last female hire, seven years earlier. At the time, there were 19 members, just 6 of them women, including her.

During her sabbatical, Christian attended a talk about diversity and inclusion at a Canadian Society for Immunology meeting at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Inspired by what she learnt, Christian and her colleagues set about making hiring diversity a priority.

By this year, her department at the Memorial University of Newfoundland Faculty of Medicine in St John’s, Canada, had managed to achieve gender parity. The changes made to hiring processes are described in a preprint posted to the bioRxiv server last month1. It has not been peer reviewed.

Christian’s department is not alone in taking action to boost gender diversity among their staff. In 2022, leaders of several departments at the University of Melbourne, Australia, reported the details of affirmative-action recruitment initiatives that led to more female hires.

And this year, the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands revealed the results of a five-year policy stating that only female applicants would be considered for permanent academic roles during the first six months of recruitment. The controversial policy led to 50% of all new hires being women, up from 30% previously.

Loneliness

When the Newfoundland project started in 2020, Christian was the only woman to have been hired in ten years. “It was a bit lonely,” she says. “You’d look around and there’d be no women on the committee you are sitting in, or it would be the same other person over and over again because there are only so many people to choose from.”

Between 2020 and 2024, the department’s job postings emphasized the equity, diversity and inclusion aspects of the application process for entry-level tenure-track faculty positions.

But the main change was anonymizing job applications in an attempt to stamp out implicit bias on search committees.

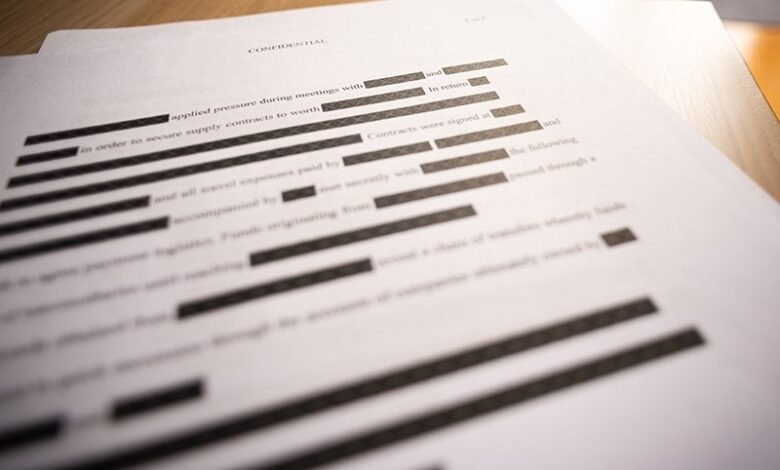

Committee members were given copies of application documents in which candidates’ names and contact information were redacted, as were references to their institution, country and leaves of absence. Gender, religion, ethnicity, race, age and nationality were also removed. This task was done by the head of the department, Mark Berry, who was not involved in evaluating candidates. His work took, on average, 90 minutes per application.

The degree type and year of completion remained, as did the location and title of any national or international conference presentations. Publication titles, including the year of publication and journal, also remained. Berry also added candidates’ authorship position in the publications and presentations.

The redacted versions were then used to draw up a shortlist of around ten candidates for each of the five roles being filled during the study period.