The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s July 2024 SCE Labor Market Survey shows a year-over-year increase in the average reservation wage—the lowest wage respondents would be willing to accept for a new job—to $81,147, but a decline from a series’ high of $81,822 in March 2024. In this post, we investigate how the recent dynamics of reservation wages differed across individuals and how reservation wages are related to individuals’ expectations about their future labor market movements.

Reservation Wages

The SCE Labor Market Survey, which has been fielded every four months since March 2014 as part of the broader Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE), provides information on consumers’ experiences and expectations regarding the labor market. The data, together with a companion set of interactive charts showing a subset of the data that we collect, are published every four months by the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data. As with other components of the SCE, we report statistics not only for the overall sample, but also by various demographic categories, namely age, gender, education, and household income. The underlying micro (individual-level) data for the full survey are made available with an eighteen-month lag.

Our measure of reservation wage comes from the following question in the SCE Labor Market Survey:

Suppose someone offered you a job today in a line of work that you would consider. What is the lowest wage or salary you would accept (BEFORE taxes and other deductions) for this job?

This question is asked to all respondents (that is, to those who are employed, unemployed, or out of the labor force). For those who are out of work, this measure provides information on the tradeoff between out-of-work transfers (such as unemployment insurance or means-tested government transfers) and expected salaries. For those who are currently employed, this measure is informative of the tradeoff between their current total compensation package (including the salary and non-wage amenities) and alternative compensation packages potentially available at other employers.

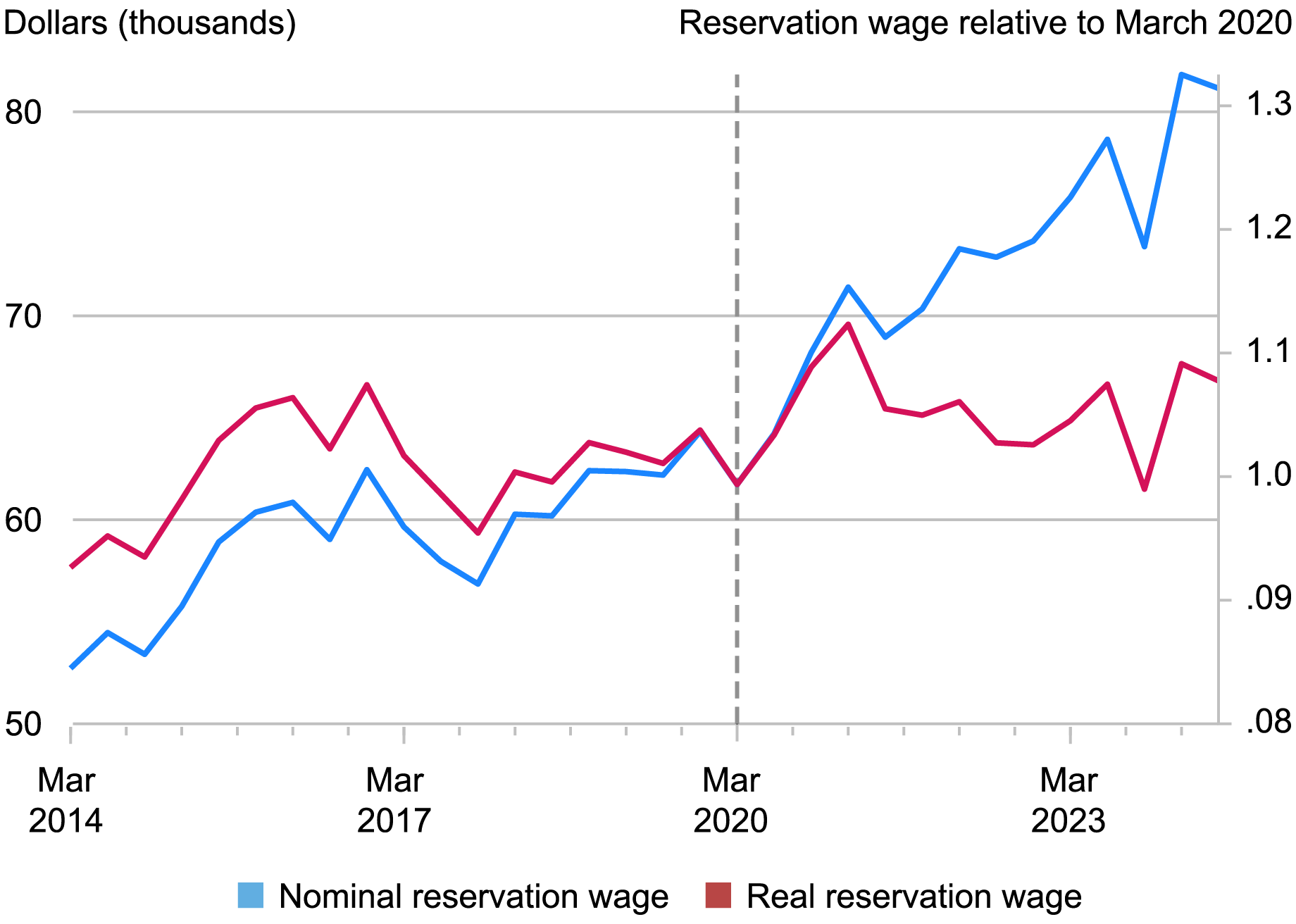

The chart below shows that the average reservation wage has increased by 31.4 percent between March 2020 and July 2024. Note, however, that this measure does not account for inflation. Deflating the series using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) indexed to 1 for March 2020, we find that the average real reservation wage increased by 8.2 percent during the same time period, while in fact it declined in the four years prior to the pandemic. This shows that even though part of the increase in respondents’ reservation wages is due to inflation, there has still been a rise in the minimum compensation respondents require to accept (new) job offers in real terms. However, it is worth noting that the average reservation wage in real terms has been essentially flat since early 2021.

The Average Reservation Wage Increased Faster Than Inflation since 2020

Note: The blue line shows the average reservation wage elicited every four months in the SCE Labor Market Survey and the red line shows the same series deflated using the CPI that is indexed to 1 for March 2020. The dashed line refers to the start of the COVID pandemic in March 2020.

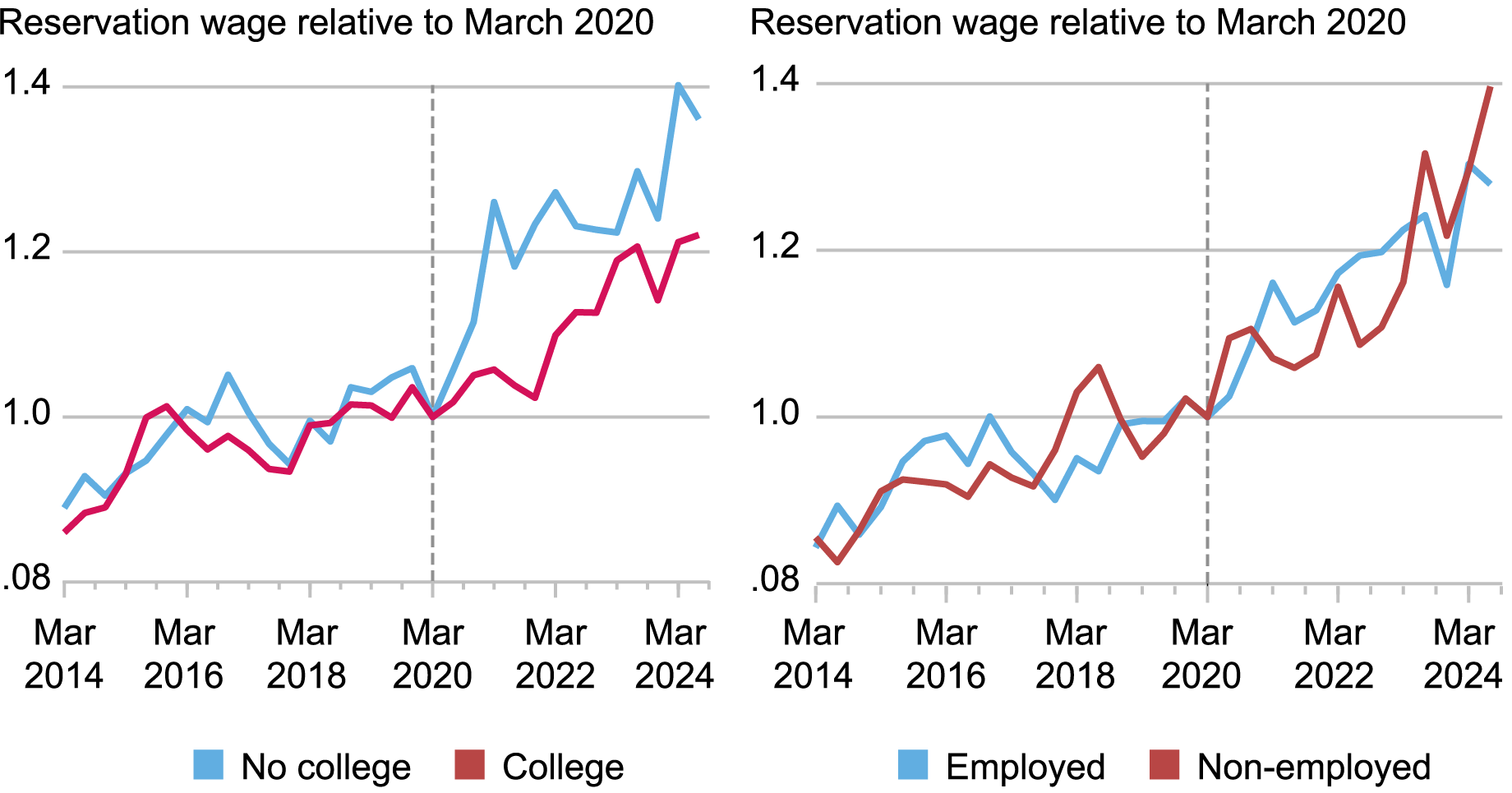

Next, we examine how this upward trend in reservation wages varied by respondents’ education and employment status. The left panel of the chart below shows that the growth in average reservation wages, relative to March 2020, was primarily driven by the respondents without a college degree up until March 2022. This implied a compression in reservation wages across education levels, since those with lower education have lower reservation wages.

Between mid-2022 and the end of 2023, reservation wages have grown faster among college graduates, reversing the previous trend in the reservation wage compression. However, since the end of last year, the reservation wages of respondents without a college degree have accelerated again. In July 2024, the reservation wages of those without a college degree were closer to those of college graduates than they were before the onset of the pandemic.

In the right panel of the chart below, we show that since mid-2022 the average reservation wage of the non-employed grew faster than that of employed respondents. This stands in contrast to the dynamics in the previous two years, as we had discussed in an earlier Liberty Street Economics post. Overall, as of July 2024, the average reservation wage growth of non-employed respondents has caught up with, and in fact exceeded, the average of employed respondents since the onset of the pandemic.

Non-employed Consumers and Those without a College Degree Experienced Faster Reservation Wage Growth

Reservation Wages and Expectations about Labor Market Flows

We next examine how reservation wages are linked to expected labor market movements. Every four months, the SCE Labor Market survey elicits respondents’ expected likelihood of being non-employed, employed, or employed with the same employer (if employed) in the subsequent four months. In the table below, we relate these probabilistic expectations to reservation wages, controlling for the respondents’ time-varying observable characteristics and for individual fixed effects.

The results show that workers with a 1 standard deviation ($44,614) higher reservation wage report 2.72 percentage points (or 32 percent) lower likelihood of moving to a new employer in the subsequent four months (column 1). On the other hand, column 2 shows that workers’ expectations about moving into non-employment do not statistically differ based on their reservation wages. For non-employed workers (including those who are unemployed and out of the labor force), we also observe that the average likelihood of moving into employment over the subsequent four months does not statistically differ based on respondent’s reservation wages.

Reservation Wages Are Meaningfully Related to Households’ Expected Job-to-Job Movements

| Employed | Employed | Non-Employed | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |||

| Probability of Moving to a New Job |

Probability of Moving into Non-Employment |

Probability of Moving into Employment |

|||

| Reservation Wage ($1,000) | -0.061*** (0.013) |

-0.011 (0.009) |

-0.022 (0.031) |

||

| Demographic Controls | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Individual Fixed Effects | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Dep. Var. Mean | 8.172 | 3.143 | 14.078 | ||

| R-squared | 0.612 | 0.604 | 0.774 | ||

| Observations | 7,253 | 7,245 | 1,164 |

Note: Robust standard errors are included in parentheses. The dependent variable column is the employed respondents’ expected probability of moving to a new job in the next four months in the first column and their expected probability of moving into non-employment in the next four months in the second column. In the third column the dependent variable is the expected probability of moving into employment for non-employed respondents. All dependent variables are measured out of 100. The demographic controls include respondent’s gender, annual household income, education, age, and job search status if the respondent is non-employed. *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

Conclusion

Results of the July 2024 SCE Labor Market Survey show a slight decline in the average reservation wage to $81,147 from a series’ high $81,822 in March. However, we find that the average reservation wage increased faster than inflation since the onset of the pandemic. Overall, the patterns suggest a compression in the reservation wage distribution by education and employment status. We also document that reservation wages are meaningfully related to households’ expectations about their future labor market movements.

Gizem Kosar is a research economist in Consumer Behavior Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sasha Thomas is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Gizem Kosar, Davide Melcangi, and Sasha Thomas, “An Update on the Reservation Wages in the SCE Labor Market Survey,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 19, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/08/an-update-on-the-reservation-wages-in-the-sce-labor-market-survey/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).