The Bell Beaker culture, named after a type of ceramic vessel, arose in Europe from around 2800 BC.Credit: Lanmas/Alamy

A western European ‘water world’ was a holdout for hunter-gatherers for thousands of years.

Ancient inhabitants of the Rhine–Meuse river delta — wetland, riverine and coastal areas of modern-day Netherlands, Belgium and western Germany — maintained high levels of hunter-gatherer genetic ancestry. This genetic signature persisted long after most of Europe was transformed into farming and animal-herding-based communities by successive migrations from the east, starting around 9,000 years ago. The findings come from a study published in Nature on 11 February1.

“It’s really an island of persistence and resistance to the incorporation of external ancestry,” says David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, who co-led the study.

Cultural integration

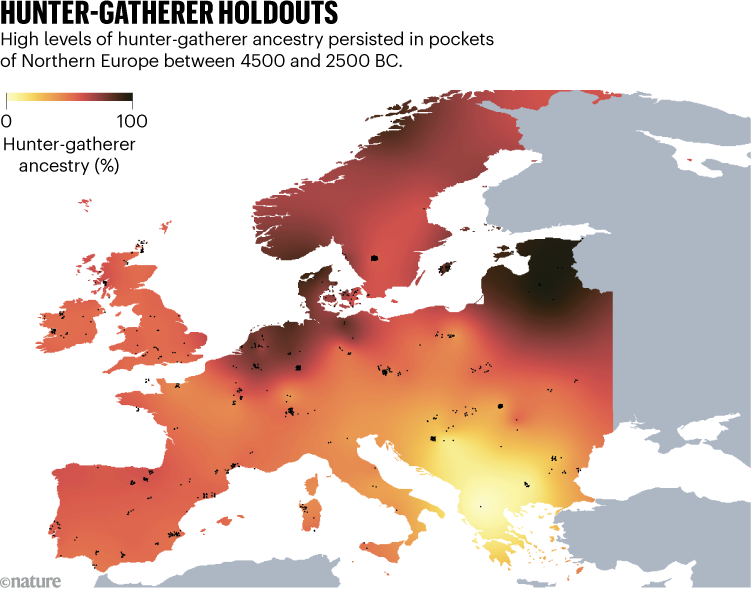

For two decades, ancient-genomics laboratories, including Reich’s, have painted Europe’s population history over the past 10,000 years in broad brushstrokes. This work showed that resident hunter-gatherers were, to varying degrees, replaced by Middle Eastern farmers, who were themselves usurped by pastoralists whose ancestry traced back to the central Eurasian steppe (See ‘Hunter-gatherers holdouts’).

But geneticists — and certainly archaeologists — knew that more fine-grained studies of individual regions would add nuance and reveal exceptions to the wider story.

Archaeological work in the Rhine–Meuse region pointed to the persistence of hunter-gathering lifestyles. But the adoption of certain farming practices as well as characteristic pottery and burial styles suggested cultural exchange, at least, with both early farmers and groups carrying steppe ancestry.

When Reich and his colleagues analysed ancient genome data from 112 individuals who lived between 8500 BC and 1700 BC, including new data from people in the region, they found that the inhabitants maintained high levels of hunter-gatherer ancestry for thousands of years after its disappearance from neighbouring regions in France and Germany, as well as Britain. A patchwork of wetlands, forested river dunes and coastline could have restricted farming, while connecting water-based communities in the Rhine–Meuse area.

When Rhine–Meuse hunter-gatherers mixed with outsiders, the researchers found evidence of a sex bias. Patterns of genetic diversity on the X and Y chromosomes suggested that European-farmer ancestry seemed to arrive mostly through females.

“We really do think that the bits and pieces of the farming lifestyle that were incorporated by these hunter-gathering groups came in through these women,” says co-author Eveline Altena, an archaeogeneticist at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

This is a surprise, says Daniela Hofmann, an archaeologist at the University of Bergen, Norway. Archaeologists will now need to work out the social forces that led female farmers to join hunter-gatherer communities.

Bell Beaker mystery

Mixing between Rhine–Meuse hunter-gatherer farmers and people carrying steppe ancestry seemed to be limited — at least initially. Elsewhere in Europe, this steppe ancestry had become widespread from around 3000 BC.